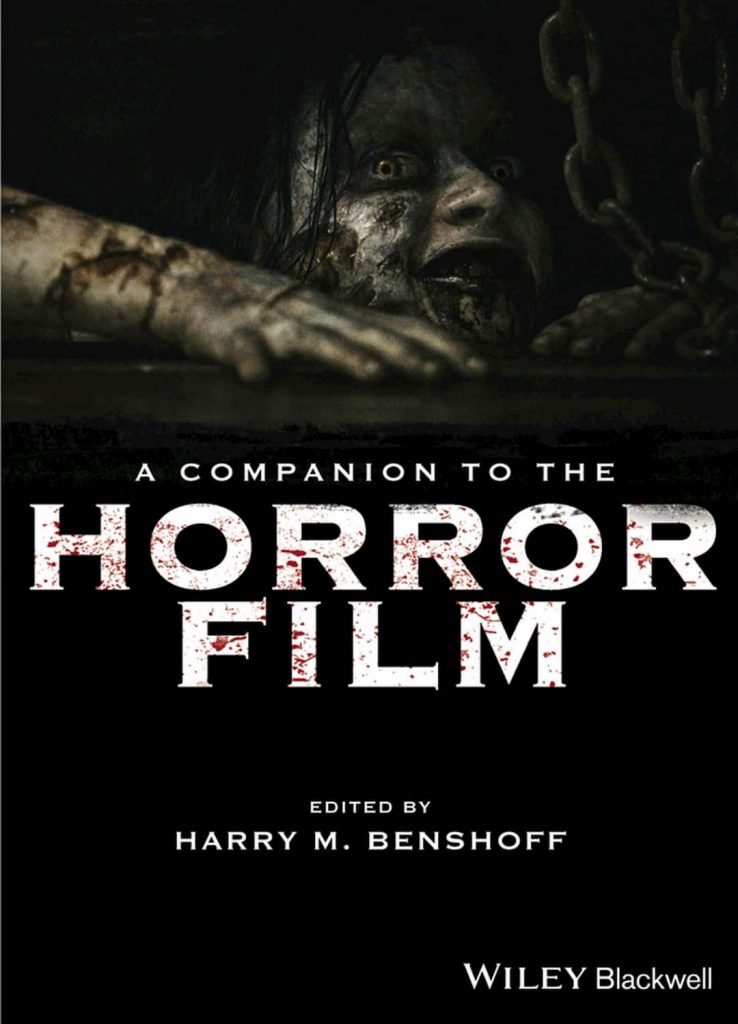

A Companion to the Horror Film: Monsters are everywhere lately .They are on movie screens certainly, although oddly enough, not always in horror films. As Adam Charles Hart’s chapter in this volume demonstrates, today monsters are at the very heart of Hollywood blockbuster action films and CGI spectacles, in franchises like The Hobbit and Pirates of the Caribbean. Monsters are also ubiquitous in animated kids films [Para Norman (2012), Frankenweenie (2012)], television programming and video games. This reflects, I think, the very fact that monsters are and always have been potent metaphors for just about any and all aspects of human experience.

In the twenty-first century alone, they need been used and enhanced interrogation techniques (torture porn), our ever-increasing surveillance culture (found footage horror films), and survival itself in a world whose infrastructure is crumbling—or at least appears to be (the proliferation of zombie apocalypse texts across all aspects of the media landscape). In its current form, the horror film itself should be somewhat ghettoized in popular culture as a critic-proof, low-class, low-budget exploitation genre aimed toward thrill-seeking teenagers, but the monsters the genre contains continue to fascinate. Putting it another way, monsters are not just for horror films anymore.

It goes without saying that the contributors to this volume understand horror films to be definitely more than low-class, low-budget exploitation flicks aimed at “impressionable” young people and/or moral degenerates. That had been (and may still be) the view of the genre held by many critics and other social reformers supposedly concerned with the genre’s allegedly negative effects on public health. As the chapters in this volume by Matt Hills, Kevin Heffernan, and Julian Petley explore, horror films have often been the instigator of “moral panics,” especially as each new generation of filmmakers seeks to outdo their predecessors in terms of gore, shock, provocation, and politically incorrect titillation. But those factors are themselves the building blocks of the genre, the blood-soaked façade that allows horror films to tackle social issues in ways no other genre can. A mainstream Oscar-winning film such as Driving Miss Daisy (1989) may take on racism in its own soft-pedaled, golden-hour kind of way, but the blood, guts, and smarts of a film such as Tales from the Hood (1995) arguably explores the topic in far more complex and nuanced ways. Horror films can say what other socially sanctioned genres often cannot. My own personal history with the horror film began when I was a child, fascinated with their images of otherness, images that I found both frightening and alluring.

Many of the authors represented in this volume speak of similar attractions to the genre. Indeed, the genre is designed to arouse intense personal responses in its audiences, and people are known to be passionate about horror, loving it as life-long fans, or hating it just as much. And while much criticism has been heaped on the genre for its alleged appeal to audiences’ sadistic impulses that argument has also been countered by others that assert that the genre affords primarily masochistic pleasures. I do not think one simple explanatory paradigm can fully explain anything in popular culture, and as such, remind my readers that whether one loves or hates the genre (or is simply neutral toward it), it probably means different things to different people.

Readers familiar with my work will discern that my predominant interests lie more in gothic horror than in slasher or gore-hound horror, but I try not to privilege one for mover the other (though it is sometimes hard not to) given the status of all horror as low or disreputable culture. As is probably obvious by now, my interests in the horror film today relate to what has been broadly called the reflective nature of film genres, and especially the horror film. That is to say, film genres do not arise or exist de novo: they are made by and consumed by people within specific historical and sociocultural contexts, and as such they “speak” to those same people about the issues of the day. The insights offered by Robin Wood (1979) (among others) within the 1970s—on how the genre functions as a sort of collective nightmare, figuring any given culture’s repressed and oppressed but even if we discount psychoanalysis—as some contemporary cultural critics would have us do—we may still invoke Stuart Hall’s (1980) “Encoding and Decoding” model: contemporary cultural approaches to film genre emphasize the semiotic and discursive relationship between texts, those who produce and consume them, and the larger spheres of culture and ideology. Cultural texts like horror films tell us facts about the cultures during which they reside: details about gender, about sex, about race and sophistication, about the body, about death, about pain, about being human, ultimately. Whether or not they speak to our repressed desires (and I think they do, whatever we understand repression to be), horror films nonetheless comment on and/or negotiate with multifarious cultural anxieties and fears, whatever they may be.